In a story commons, we explore what was, what is and what could be

This piece is part of our ‘Lessons for a Story Commons’ series. These lessons emerged from a group of creatives who gathered to share examples and prompts for shifting the way we tell stories. Read more about this process, and the transition we’re working towards, in our introductory piece.

Illustration by Charlotte Bailey

The People’s Newsroom has been exploring how storytelling can support transitions away from extractive economies and towards regenerative and life-giving ones. A theme that came up in our learning together was the importance of stories about emerging futures being located in specific places, histories and communities.

This chimes with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) views on the role of stories in keeping the planet at a liveable temperature: “Narratives that help explain where a community is, where it wants to go and how it intends to get there are an important enabler of transformation"[1]. It’s significant that the IPCC doesn’t call for a single narrative for the whole world, or even a whole nation, but for community-level narratives.

Transitioning away from extraction will look different for different groups and in different places, depending on specific cultural and physical heritages. And while communities of place won’t be the only communities that matter, reconnecting to place is going to be a massive part of any transition, as our economies, food systems and industries ‘re-localise’.

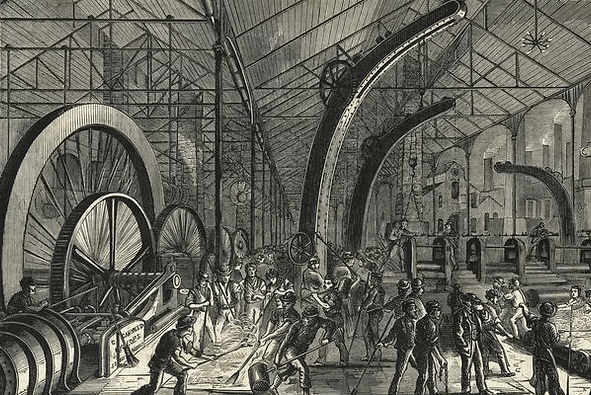

A 19th century steel factory in Sheffield

We’ll need to draw on these different realities of life in the city to tell a new story about where we’re going. And we’ll need practices to bring the stories together and weave them into textured narratives of how we got to where we are, to learn from what we’ve inherited so that we can begin to explore new possibilities.

Needless to say, conventional ways of doing journalism and presenting ‘news’ do not really support this kind of story-sharing, which is deeply rooted in specific times and places. In fact, they often do the opposite.

What was: histories are ignored, obscured or devalued

Think of how ‘news’ focuses on the things that just happened, rather than beginning with background and context. This is counterintuitive and confusing, and makes it hard to understand the links between past and present. [2]

Think of how audiences are led to empathise more with people in stories where there is more history and explanation given for their actions. And think of how some places are implicitly made less important because they’re presented as if they’re ‘behind’ others, not yet caught up to the present, even if they may actually be giving us important signals about what the future holds.

What is: the present is misrepresented

Think of how what is ‘newsworthy’ prioritises spectacular and unusual events, even though it’s routine and long-term processes that often shape our lives most profoundly. Think of how the most important stories are ‘national news’, and are often presented as if they aren’t really happening anywhere, as opposed to ‘local news’, which is deemed less important because it’s happening ‘somewhere’.

And think of how journalists are trained to stick to their ‘beats’ rather than making connections: how financial journalists don’t cover climate change even though the economy is driving climate breakdown.

What could be: the future is none of their concern

Think about how embroiled our media companies are with the status quo, and how often their structures have been used to undermine movements aimed at shifting power away from billionaires. Think about how common it is for journalists to say they have to ‘stick to the facts’, and can’t speculate on what kind of future may be desirable – even though this just implies that the status quo will continue.

Think about how, when we do get visions of the future from the tech oligarchs, they’re visions of everyone everywhere using the same technology to become less connected and committed to the places they live.

Our vision for alternative forms of story-sharing that can support the transition towards a livable planet is what we’ve been calling ‘a story commons’. Rather than always being stuck in this misrepresented present, in a story commons our stories will pay much more attention to the origins and patterns that are informing where we’ve arrived.

And our stories will centre the interconnections and entanglements between different areas of life, so we can understand how we’re impacting the living world and practice living differently.

In our learning cohort, we heard examples of organisations and communities putting this into practice. We heard about the community-created film that came out of National Theatre Wales’s project in Pembrokeshire (Go Tell The Bees), which wove together local memories of the Sea Empress oil spill in the 90s, Celtic mythology, and an imagined future where bees are leaving humans behind.

From CIVIC SQUARE, we heard how they were rooting their work in Ladywood, Birmingham around new understandings of the present, such as through their ‘neighbourhood portrait’ based on Doughnut Economics. And how they were planning to connect the area’s industrial past with a regenerative future through community retrofit of a disused warehouse, using biomaterials from the local region. The group have told these stories to the community more widely through their Good News of B16 news-sheet.

In Sheffield, our cohort member was Now Then magazine, which is also hosted by Opus. Because of this relationship with Opus, which is dedicated to transformative systems change in the city, Now Then has a more explicit vision for change than many newsrooms, which affects the kinds of stories it tells and how it tells them.

One example of this has been stories supporting work on the Sheffield City Goals, which were agreed in early 2024 and which are framed around “six stories we want to be able to tell in 2035”. Opus has done much of the behind-the-scenes work on this project and Now Then has supported this, such as through publishing an Honest Conversations series about the challenges facing the city.

These stories used generative journalism methods to orient the conversations towards new possibilities, and to encourage local leaders to speak to and connect with the issues on a human rather than just an institutional level.

Now Then has also carried extensive coverage of Palestine organising in the city, especially among local councillors and protests by students and academics at both universities. This coverage has helped raise awareness of the involvement of Sheffield-based companies and the city’s universities in weapons manufacturing, including making parts for F-35 planes which have been used in the genocide in Gaza and attacks on Yemen.

People protesting outside the Magna Science Adventure Centre in Sheffield

Weapons have been a big part of Sheffield’s history – the city was once known as the artillery factory of the world – and while the industry employs few people now, it’s still central to the local growth strategy. Now Then is currently exploring what further support it could give to anti-arms campaigning, and how to link this up with other conversations about transforming the economy in the region to one that’s regenerative for people and planet.

There's an important difference between this approach and ‘traditional’ journalism: Now Then is reporting on things that people are trying to make happen, not just things that have happened. Traditional journalism usually avoids talking about things that might happen because it sees them as ‘non-factual’ – but in a context of rapid change, ‘facts’ aren't and can't be everything.

This doesn't mean that ‘anything goes’. To the contrary, acknowledging an investment in particular kinds of futures can lead storytellers to hold new kinds of responsibility for the content, absences and effects of the stories being told.

Like other newsrooms in our cohort, Now Then is a member of the independent press regulator IMPRESS, which means the public can have access to free arbitration if they have serious complaints about its coverage. But the team have also recognised the need to build much more responsive and relational accountability with their readers, including mechanisms for their audience to be part of setting the agenda for the magazine.

Partly inspired by Greater Govanhill, another member of the cohort, they’re trying to create more forums to foster these relationships (if you live in or near Sheffield and want to be involved, get in touch here).

As the example of Now Then’s Palestine coverage shows, being ‘connected to place’ shouldn't mean being inward-looking. All places are connected to others, and in fact this is often how extractive systems keep going: by moving the violence of harm somewhere else.

In a story commons, we draw on feminist and indigenous thinking, recognising that all knowledge comes from ‘somewhere’, and it is through our connections to land that we can learn to live collectively within our planetary limits.

And it is through commoning our stories that we can bring those distant-but-connected realities into our everyday awareness, and our understanding of what was, what is and what could be, right where we’re standing.

Questions we’re asking now:

How can storytelling hold the past, present and future all at once? In a moment where there is content overload, how do we center and surface what’s most valuable? – Megan Lucero

How do we explore the systemic while also being rooted in place? – Shirish Kulkarni

This piece is a reflection of the learnings and insights shared in dialogue with the People’s Newsroom community. It was curated and written down by Debs Grayson and shaped by Shirish Kulkarni and Megan Lucero, edited by Sam Gregory, and produced by Phia Davenport.

This piece is part of a series, Lessons for a Story Commons. Aside from the introduction, How storytelling can open the door to thriving futures, the series can be read in any order:

Endnotes

[1] IPCC Sixth Annual Report 2022, Chapter 1, Section 1.5.1 (p.175)

[2] You can read about Shirish’s alternatives to the inverted pyramid structure here.